The Origins of Our Fascination with True Crime

How one change 300,000 years ago led to the true crime craze

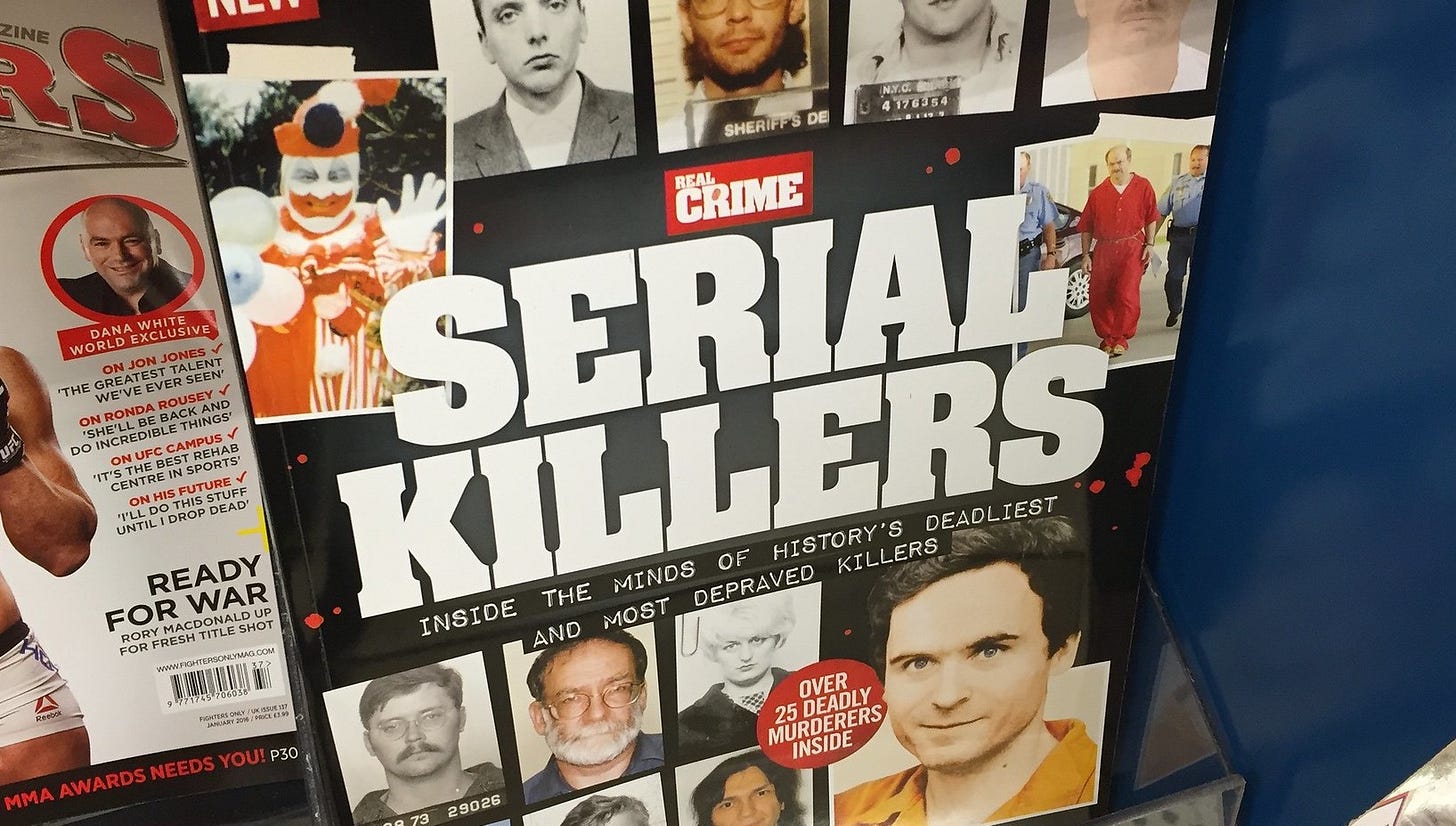

Photo by Matt Brown on Flickr.

Why are we so fascinated with serial killers and true crime?

I get this question often, so I thought it would be worth writing about some of my thoughts on it. One of the dimensions of morbid curiosity that I’ve discovered, the “minds of dangerous people” dimension, maps directly onto our love of true crime. Like other types of morbid curiosity, our interest in serial killers and true crime has its roots in gathering information about threats and potential dangers.

Recently, I’ve been exploring how one particular shift in human society that began around 300,000 years ago may have led to our fascination with true crime. To understand this shift and how it may have led to our collective fascination with true crime, we first need to talk about human aggression.

The Two Faces of Aggression

It’s remarkable that humans don’t impulsively kill each other more often. Whether it’s in the pit at a rock concert, standing shoulder-to-shoulder on city buses, or in an aluminum tube 30,000 feet in the air, humans often find themselves in tight quarters with total strangers.

Millions of instances like this occur every day with very few acts of aggression. We take this for granted, but it’s a peculiar phenomenon for a primate. Evolutionary anthropologist Sarah Hrdy once remarked that if a plane full of chimpanzees ever managed to leave the tarmac, it would be a miracle if any of them survived the flight. The aisles would be flowing with blood and severed body parts before the plane landed.

To be clear, humans can be aggressive. But, we are not aggressive in the same way that Chimpanzees are aggressive. Chimpanzees, like many primates, have a social hierarchy that is enforced through reactive aggression. If another chimp challenges or doesn’t defer to the alpha, the alpha will respond violently. The bigger, stronger chimpanzee is reactively aggressive because this quick, violent response to a transgression works well to maintain power.

Human hierarchies don’t work like this, at least not usually. Social rules often regulate reactive aggression and punish those who can’t control their violent outbursts.

Biological anthropologist Richard Wrangham argues that, beginning around 300,000 years ago, humans tamed themselves when they began conspiring to execute reactively aggressive males. It seems a bit paradoxical to say that we became tame through violence (hence the title of Wrangham’s book, The Goodness Paradox). Killing aggressive males requires… aggression. So, how could killing aggressive males possibly have led to the domestication of our species?

The answer lies in the fact that there are two kinds of aggression.

Reactive aggression is an immediate, impulsive response to a perceived threat that is fueled by anger or rage. This is common in the animal kingdom but rarer in humans.

Proactive aggression, however, is rarer in the animal kingdom and more common in humans; it’s colder and more calculating rather than impulsive. Proactive aggression requires some planning and foresight, skills at which humans excel. This allows humans to withhold their response to a transgression or threat until the time is right, when the costs are low.

Because proactive and reactive aggression are mediated by different neural substrates, it is possible for tendencies toward one type of aggression to be selected for over the other. When humans began conspiring to violently oust reactively aggressive males, one consequence was that those reactively aggressive males lost their status and had their reproductive fitness lowered. This resulted in fewer genes for reactive aggression floating around in the gene pool. Over thousands of generations, this had a noticeable impact on how reactively aggressive our species was.

While the reduction in reactively aggressive tendencies in the human population is interesting, it’s the flip side of that coin that I want to focus on here. Those males who were cooperating to overthrow the reactively aggressive males were also increasing their own reproductive fitness. This means that the prevalence of individuals with a predisposition for positive traits like impulse control and cooperation increased — but so did the prevalence of individuals with a predisposition for proactive aggression.

91% of men and 84% of women have vividly fantasized about killing someone at least once in their life.

New Signs of Danger

With the decline of reactive aggression and the rise of proactive aggression, a problem began to emerge: cues of aggression were no longer straightforward. Reactively aggressive are typically larger, stronger, and have wider faces. They have a short temper and lash out in anger at perceived transgressions. These physical and behavioral traits signal to us that an individual is reactively aggressive. Our minds have evolved to pick up on those signals.

Examples of low and high facial width to height ratios. Higher ratios (wider faces) are perceived to be more aggressive. Figure 5 from Hehman et al., 2015.

Proactively aggressive individuals don’t have these physiological and behavioral cues. Instead of one’s propensity for aggression being given away by their short temper or wide face, it was now hidden away in the mind, festering until the time was right to strike. Proactively aggressive individuals could brood over a slight and envision how to kill another person without tipping them off.

The consequence of this shift from reactive to proactive aggression has left its mark on the human psyche and can be seen in the minds of people today. In a massive international study that included over 5000 individuals, evolutionary psychologist David Buss and his colleagues asked people if they had ever fantasized about killing someone and, if so, to describe the fantasy. The researchers came across a shocking discovery: 91% of men and 84% of women had vividly fantasized about killing someone at least once in their life.

The majority of people in the world never commit murder, but most of them have thought in detail about murdering someone. The psychological mechanisms that produce proactive aggression are churning away in the mind of every person. If the circumstances were right, who knows how many of these violent fantasies might materialize.

For the past few hundred thousand years, humans have had to adapt to this new threat. We could no longer solely rely on the cues of reactive aggression that we had evolved to recognize. We now had to actively learn novel cues of proactive aggression. Reactively aggressive people intentionally signal their aggression; proactively aggressive people intentionally hide their aggression. We needed to interrogate contexts in which proactive aggression occurred. What caused the conflict to precipitate? Were there any clues in the behavior of the aggressor beforehand? What was going on in their mind to make them do this?

In other words, we needed to become curious about the minds and behaviors of dangerous people.

Quenching our Curiosity about Killers

True crime draws its popularity and success from our mind’s thirst for knowledge about proactively aggressive people. Listening to or reading true crime stories is a low-cost way for us to learn what kinds of behaviors or mindsets are common among proactive aggressors. We are in no physical danger when we consume true crime, so we can easily and cheaply gather information about the killer’s mindset, motivations, and behaviors. True crime also offers a simulation of an event for us to learn from and mentally rehearse. What would we do if we found ourselves at the mercy of a brutal serial killer? Would we find a way to survive?

Early versions of stories that we recognize today as true crime were sung in medieval ballads and transmitted through oral stories. It wasn’t long after the invention of the printing press that written stories resembling modern day true crime began to emerge. Sensational and graphic stories of murder filled the pages of pamphlets beginning in the 1500s.

One of the early examples of this came from author and Lutheran minister Burkard Waldis. In 1551, Waldis published a story of how a woman savagely murdered her four children.

She first went for the eldest son

Attempting to cut off his head;

He quickly to the window sped

To try if he could creep outside;

By the legs she pulled him back inside

And threw him down on the ground;

He got up and away he did bound

The story continues with the mother chasing her eldest son, axe in hand. She eventually finds him hiding in the cellar and hacks away at him. Her other three children suffer equally gruesome fates before the story comes to an end.

The pamphlet describes the scenes and the children’s attempts to escape in great detail and even includes images of the scenes in woodcuts. Readers devoured the details of this gruesome story, despite already knowing the outcome from the overly descriptive title: A true and most horrifying account of how a woman tyrannically murdered her four children and also killed herself, at Weidenhausen near Eschwege in Hesse.

With access to vivid details of how the woman murdered her children and how the children failed to escape, readers could imagine for themselves what they would have done differently in the situation. Would they have made it out of the house, or would their deranged mother have hacked them to bits in the cellar?

A more psychologically-centered version of the true crime story rose to prominence in English ballads and pamphlets as early as the late 16th century. The focus of the story shifted from the description of the crime to the mind and behaviors of the person who committed the crime. The psychological motivations of the killer are now a central ingredient of the true crime genre. The audience wants to know what the killer was thinking, how they acted before the crime was committed, and if they gave any clues about their violent nature.

The structure of modern living also plays a role in the popularity of true crime and the allure of the potentially dangerous man next door. Most features of the human mind evolved in the context of smaller group-living. For most of human history, people knew their neighbors quite well. Neighbors were extended family members, friends, and other members of a tight-knit group. You would hunt, gather, feast, and engage in communal rituals with your neighbors on a regular basis.

Strangers existed, and we interacted with them, but they didn’t live next door or down the hall from us. Strangers certainly did not make up the majority of those surrounding you like they do in a modern city. Strangers were also not treated the same as members of your local community. With their intentions unknown, strangers would be met with more skepticism and caution.

As populations grew, people in many parts of the world began living in closer proximity to strangers than any of their ancestors could have imagined. Today, many of us are surrounded by people we don’t know at all. We still deal with this much better than our primate cousins might, often giving strangers the benefit of the doubt when it comes to following the norms of society. Crammed trains and fully-booked restaurants exist without descending into chaos. However, the potential of a dangerous stranger next door still lurks in the back of our minds.

Most of us don’t automatically assume the guy next door is a killer, but small cues in his behavior might have us questioning if he has bodies buried in his basement.

If you enjoyed this post, be sure to check out Chapter 3 in my new book, Morbidly Curious: A Scientist Explains Why We Can’t Look Away. In it, I go into detail about my theory on why we are fascinated with true crime.

As a reminder, if you send me a screenshot of your book order, you’ll get 3 months of the paid version of my Substack for free. That’s an $18 value for free when you purchase a $19 book. You can send the screenshot to MorbidlyCuriousBook@Gmail.com.